1Originally published in Semiotica 41 (1982): 107-134.

Introduction

2For a good two decades we have been hearing about a “linguistic turn” in philosophy. This turn is based on the thesis that language is not just one more topic of philosophical interest among others, such as nature, history, art, and mathematics, that are dealt with by so-called hyphen-philosophies, philo|sophical disciplines of a second level, but is, as a condition of knowledge in general, the primary object of a prima philosophia. In Germany we have come to use a word that supposedly goes back to Nietzsche to sum up this transcendental role of language, a word for which other languages have trouble finding a concise equivalent. This slogan is that of the Nichthinter|gehharkeit der Sprache, “the nonunderpinnability of language” by nonverbal modes of cognition, as one might tentatively try to translate it. Thus, language has finally received an honor that most of the other topics I just mentioned have received at one time or another, from one philosophical school or another. Think of the philosophies that have promoted Life, History, Art, or Science to the status of the central philosophical theme. And just this fact is enough to make us a bit skeptical.

3Karl-Otto Apel (1963) went furthest in his now 20-year-old book on the idea of language in the humanistic tradition from Dante to Vico: Language, which cannot be based on nonverbal cognition and which is on the contrary constitutive for our knowledge of the world, is our particular mother tongue. The categories of thought thus lose their universality. They are not “determined once and for all for all men”. They change from one “historical linguistic community” to the next (1963, 26). In order to explain the happy fact that Japanese are most certainly capable of understanding and thinking productively in terms of Newton’s physics and Descartes’s philosophy, Apel claims that they must have previously taken over the “mother tongue of the Western mind”, which functions as the metalanguage of modern physics and metaphysics. This view exhibits a wide variety of holes:

- There is no reflection on the possibility of acquiring colloquial language in addition to that of the culture into which one is born, either immediately, when a child is suddenly set down in a new language community, or indirectly, on the basis of translations and paraphrasings of foreign languages in one’s own language. It is obvious that neurological and cognitive structures predate the acquisition of language, structures that allow, at least at some specific stages of development, any natural language to be completely acquired. One must ask, to what extent might the reciprocal translatability of languages be, if not made possible in the first place, at least made easier by the existence of linguistic universals?

- There is also no reflection on the question of the extent to which there are universal aspects of colloquial languages that account for their role as the last metalanguage of formalized scientific languages. The shift with reference to the Hegelian postulate of a parallelism between the “system of philosophy” and the “history of philosophy” that we are currently witnessing provides food for thought. It would appear that the systematic structure of a scientific field is not mirrored in the history of science, but rather in the prescientific phases of cultural development on the one hand and in the ontogenetic development of the prescientific intelligence of the child on the other hand, and that both of these exhibit universal aspects.

- The variability of every natural language must be thematized in this context. Every linguistic code breaks down into a series of subcodes, any of which, depending on the addressee (“sociolect”) and object of the speech (“technical language”), may come to the fore. Individual technical lan¬guages can exhibit a strong foreign influence. Even Apel (1963, 41) has recourse to the “translatio" of the concepts originally formed by the Greeks [...] in the modern European languages” for his thesis of “the vernacular sense-a priori” of Western philosophy and science. The effortless “switching” from one verbal subcode to another belongs to our natural linguistic competence, as does the matter-of-course possibility of supplementing the mother tongue in the narrow sense by foreign languages, often by a lingua franca that opens up access to a wider world.

4Reservations related to this third argument led the Erlangen School (Paul Lorenzen, Wilhelm Kamlah, Friedrich Kambartel, Kuno Lorenz, Jürgen Mittelstrass, et al.) to shift the nonunderpinnability thesis from the level of colloquial language back to that of linguistic competence as such. “We cannot get behind language only in the sense of linguistic competence ...” (Mittelstrass 1974, 200). This improved thesis is supplemented and made more precise by a thesis that is typical for theories of language that are oriented toward logic: “We cannot get behind predication as a funda|mental linguistic action” (Mittelstrass 1974, 157). Neither the improved thesis nor its supplement can be maintained.

5My paper as a whole is directed primarily against the widespread linguistic determinism, connected with the names Humboldt and Weiss|gerber in Germany and Sapir and Whorf in Anglo-Saxon countries, accor|ding to which there is a priority of language in the relation language/thought: The general world view, not merely the intellectual but also the sensual, and thus our whole experience of the world, is dependent on language. But the handy formulations of the Erlangen School with respect to the usually only vaguely formulated thesis of the Nichthinter|gehharkeit der Sprache is an invitation to make their work the guiding thread of a critique, all the more so in view of the fact that the image of a “wildly grown” natural language — a view the Erlangen School shares with most other language theorists who are oriented toward formal logic — will be subjected to a hard criticism in the course of the argument.

6But I must hasten to add that the Erlangen view concerning the determination of relations between language and thought is not so clearly laid out in their texts as one might expect, in view of their otherwise very meticulous mode of argumentation. There are places according to which a knowledge of objects and an understanding of language go hand in hand: “I come to know them (objects, e.g., music instruments such as bassoon and clarinet) in that I learn to distinguish them, the words and the instruments, simultaneously” (Kamlah and Lorenzen 1967, 30). Other texts seem to suggest that in their view only intersubjectively reliable distinctions are necessarily of a verbal nature. In this case only the intersubjective reliability of prelinguistic distinctions, not their existence, would be denied. The following quotation allows both interpretations, depending on whether we refer the sentence between the dashes to the narrower or wider context. Both versions seem to me to be false.

7The reliability which is patent in the case of colloquial language, and which must be established for its technical use, does not rest on the fact that we already know something about the world before we know something about our language — he who speaks in this way is on the side of the nymphs and metaphysicians — but on the fact that it can be seen to be a consequence of a common control of common linguistic usage. (Mittel|strass 1974, 202).

8A third type of statement also concerns expressis verbis only the quality, this time the justifiability, not the existence, of preverbal distinctions: “The assertion that the world is characterized by the “return of the same” independently of our linguistic distinctions, thus “in itself”, cannot be justified. The attempt to justify it would immediately make use of linguistic distinctions and thus move in a circle” (1974, 156). Mittelstrass seems to ignore the fact that a perceptual distinction can be confirmed intersubjectively not merely in terms of a corresponding verbal behavior, but also — and genetically, generally earlier — by means of a corres|ponding motor behavior.

The underpinnings of language competence

9The Erlangen School explicates language competence in terms of the ability to make distinctions, to differentiate. This explication already expresses the central status that is given to language. Modern philosophy, under the influence of Locke, had a different view. Language was not primarily a means of making differentiations, but rather a means of combining and fixing. As a sensualist and atomist, Locke presupposed a universe of disparate sense-data to which simple ideas correspond. The task and achievement of language consisted in its ability to fix and perpetuate useful combinations of such simple ideas into complex ideas. Without a word such as “triumph”, we would, according to Locke, hardly be able to hold the various properties of such an event together.

10In order to be able to offer the Erlangen solution as a third way and as a way out of the two diametrically opposed and equally unsatisfactory positions, Mittelstrass makes use of a considerable reinterpretation of notions that have come to have fixed roles in the history of philosophy. Realism and nominalism stand opposed to one another. According to the realist position — as Mittelstrass would have it — the world is “in-itself” completely articulated prior to all linguistic differentiation. According to the “position which is traditionally called nominalist”, it is totally undifferentiated. But the nominalists were until very recently too mentalistic and too empiricist in orientation, in short, too devoted to good common sense, to accept the assumption of a universe that is completely undifferentiated prior to language that Mittelstrass attributes to them. The idea of reality as an undifferentiated, arbitrarily divisible continuum as a familiar figure of thought is of very recent date, and more popular in the humanities and popularized philosophy than among professional philosophers. The historical situation is rather the following. For both realism and nominalism, the universe is articulated or articulatable prior to all verbal intervention. For nominalism, all segments of the universe are of equal value and thus are arbitrarily combinable. What is combined, and how, depends only on the particular interest and considerations of usefulness. For realism, not all segments are of equal value and equally combinable. The inner structure of the segments (physical segments in the case of matter, logical-semantical segments for the ideal) is decisive for what, how, and in what order things can be combined. Not external considerations of usefulness, but properties that are inherent to the individual elements and the elementary relations between them are decisive for the actually realized combinations. There are compatibilities, incompatibilities, affinities, and preferences immanent to the individual phenomena.

11According to Mittelstrass (1974, 150, 156ff., 166ff.), every statement concerning a preverbal differentiation of the world that might serve as a reliable foundation for a verbally formulated differentiation leads to tautologies. This objection is too easy. It is obvious that one cannot talk about preverbal differentiations and elaborate a verbally articulated theory about them without formulating these preverbal distinctions verbally, in language. It goes without saying that it is impossible to “talk about the world without (verbal) distinctions” (1974, 157). But the question is: can preverbal distinctions of the world be determined intersubjectively only verbally or also, and perhaps primarily, extraverbally? Can one come to an agreement concerning distinctions one sees only via language or also extraverbally, namely, by means of different modes of behavior? We do not conclude that an animal distinguishes the ringing of a gong from the blast of a trumpet on the basis of a message in animal language, but on the basis of differing motor responses. If the language determinists were right, then Pavlov’s dogs and Skinner’s rats would be one up on us poor humans: they and they alone would have a nonverbal competence to distinguish. The difference between man and animal would not consist, as has been assumed, in the fact that certain kinds of animals have a sensual ability to distinguish in areas such as the infrared region of the cooler spectrum that surpasses human capacities, but rather in that man and animal have two categorically different capacities to distinguish. Knowledge in its ele|mentary form consists in a mental (not purely physical) differentiation or identification and combination of phenomena: “Knowledge then seems to me to be nothing but the perception of the connexion of and agreement, or disagreement and repugnancy of any of our ideas [...]. For when we know that white is not black, what do we else but perceive, that these two ideas do not agree?” (Locke 1690, §4.1.2).

12Mittelstrass speaks repeatedly of the necessity that the reliability of verbal distinctions be demonstrated and successively extended. Reliability is “the consequence of a common control of common linguistic usage”. “This control takes place by means of the correction and refinement of already accepted distinctions in (re-)constructive verbal regimentations, ...” (1974, 202f.). Such explanations operate on much too high a level of language. This kind of justification — “interconceptual” consistency plus intersubjective consensus with regard to this consistency — is found primarily in higher-level, complex verbal structures. This can be exhibited most clearly in terms of cipher systems. The Indian-Arabic system of ciphers is superior to the Roman system, since it is more unitary and transparently constructed. It more consistently makes more relations between the individual numbers visible than does the Roman system. Compare the ciphers for “forty-four” and “eighty-eight”: 44 — 88 versus XL.V — LXXXVIII. Ones and tens are symbolized in the same way in the Indian-Arabic system, and appear in positions that always remain the same, which is advantageous not merely cognitively, but also operatively, in carrying out mathematical operations. According to the extreme nomi|nalistic point of view, we would have no reason to use the cipher 120 for the number our language calls “one hundred twenty” rather than the number “seventy-seven”. An object has no more and no less in common with the one than with the other. The number 120 would exhibit no more and no less similarity to the numbers 100 and 20 than to the numbers 70 and 7.

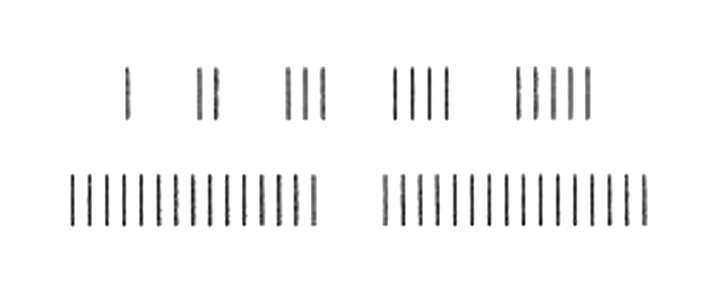

13The criterion of inner-linguistic consistency, which is so important for the construction of a regimented language, is valid only for the so-called “complex ideas”, which can only be grasped and distinguished from one another semiotically. Relatively simple phenomena, on the other hand, can be distinguished intuitively and, if they are sensuous phenomena, perceptually. A classic example is given in Figure 1: one to five/six strokes can be kept distinguished from one another by the eye alone, 15 and 16 on the other hand, only semiotically, with the help of a linguistic or extralinguistic sign system.

14The radical thesis that language functions as the all-pervasive deter|miner of our experience and view of the world must be replaced by a compromise thesis in view of simple perceptual paradigms such as those just mentioned, of Locke’s analogous analysis of numbers (1690, §2.16.3.—6.), and of a growing amount of psycholinguistic observations and tests concerning the acquisition of language: the simplest verbal distinctions are carried by prior perceptual and cognitive distinctions, while more complex cognitive structures are semiotically-linguistically constituted and thus also determined. The “mode of givenness” of the number “ninety-nine” is different in the Indian-Arabic cipher system than in the Roman. In the latter it is not referred to the number “hundred” (IC), a “difference of meaning” that clever businessmen take advantage of by offering articles for §99.00. But we must not lose sight of the fact that, as Leibniz (1765, §2.16.5) notes with respect to Locke, the semiotic-linguistic constitution of “complex ideas” is only possible when it takes place systematically, i.e., when the constitution of the sign system itself is cognitively transparent in its structural principle. We would not get far in the construction of the series of natural numbers if we exchanged ciphers such as 77 and 120, or introduced arbitrary signs such as “abracadabra” for 77 and “jungili” for 78, etc.

15If the language determinists were right, then children learning language would start with verbal expressions they hear from adults and then analyze their visual field for objects and events that might correspond to the expressions. They would differentiate the world to the extent necessary for their understanding of language or to the extent that their understanding of the language makes possible. Psycholinguistic discoveries suggest that in the earliest phases of language acquisition the situation is just the reverse. A child selects, out of the many verbal utterances he hears, those that refer to phenomena with which his own behavior shows that he is perfor|matively, perceptually, and cognitively familiar. The child picks up the word “mouth” after its own, that of its mother, and that of its dolls has come to function as a well-determined point of reference for various actions (cf. Bruner 1975). This cognitive basis holds not only for indi|vidual words, etiquettes, but equally for grammatical structures. Familiarity with the structure of an action guides the child in the analysis of elementary sentences and misguides it in its own understanding of higher-level sentences that depart from this structure, such as when the main figure of a situation functions not as an agent, but as a patient.

16Two epistemological errors lie at the bottom of the Erlangen philo|sophy of language:

17(l) The realistic opponent is charged with an unreflected circular argument, but simultaneously there is a hysteron proteron fallacy in the presentation of their own position. Every intersubjective understanding of linguistic distinctions presupposes an intersubjectively unitary perception of linguistic signs, a nonlinguistic, perceptual distinction of sensuous figures that function as signs. If one takes the Erlangen School at its word, we would be able to distinguish the phonemes t and k in “tape” and “cape”, which a child demonstrably cannot distinguish in an early stage of language acquisition (cf. Holenstein 1976b, 191), only after we have (meta-)linguistically learned the distinction. The consequence is an infinite regress, or the impossibility of introducing a distinction that involves sensuously perceivable signs.

18It is worth taking a look at the question whether we could and would distinguish sensuous phenomena that have no function for us. Would we learn to distinguish sounds such as t and k if this distinction had no function, in this case the function of discriminating meanings? Experimental research has shown that sound differences that are merely phonetic and not phonemic, and thus have no function in distinguishing different meanings, are (easily) overlooked (cf. Holenstein 1976a, 55, 57). Here we run into two problems. One, is it at all possible to apprehend something purely as functional? Two, does not every perception of a sensuous-property also have a functional moment?

19With regard to the first problem, does not the apprehension of a functional possibility imply, if not a prior, then at least a simultaneous perception of a shape? Can a ball be recognized as something that can be rolled, as something that can fulfill a function with reference to the motor abilities of the subject, without certain perceptual properties being co|experienced, e.g., that it is a more-or-less round object? A ball stands out as such against the more or less diffuse perceptual field in that it can be made to roll. It is well known that a child who has this experience repeats the action immediately and several times, if he happens to come across appropriate objects. But recognition is only explainable if a perceptual apprehension of the object of the action is tied to the exercise of the motor action.

20With regard to the second problem, it would appear that under radical analysis, the (motor) functional and the (perceptual) structural apprehen|sions turn out to be two aspects of one and the same process. Visual perception itself is an active process. A shape is not apprehended immediately “ready made” as a whole, but is constituted in successive phases. The visual perception of a ball as a round object is accordingly, in turn, a functional phenomenon. Seeing a round ball activates and satisfies our sight just as the rolling activates and satisfies our motor capacity. Seeing is for the eye what moving is for the hand, what eating is for the palate and stomach: a kind of nourishment.

21(2) Erlangen School publications read as if outside of the universe of discourse (the world as it is verbally articulated), only a reality in-itself is thinkable. However, we do not refer to the world in-itself in language, but rather to the world as subjectively and intersubjectively perceived, remembered, phantasied, thought, in short, the world of which we are in some way conscious. The claimed immediacy of the relation between a verbally articulated world and a world as it is in-itself leads to a circle in the definition of truth, if one attempts to explain the truth of a sentence in terms of the reality of the state of affairs expressed by the sentence: “A state of affairs is a real state of affairs if and only if a statement which represents it is true. An assertion is true if and only if the state of affairs which it represents is a real state of affairs” (Kamlah 1962, 120). The Erlangen School avoids the circle by making the definition of truth independent of the concept of reality via recourse to the consensus that a sentence intersubjectively gives rise to among “everyone competent in the language and subject matter who makes an appropriate verification” (Kamlah & Lorenzen 1967, 116ff.). The concept of reality is, then, in accordance with the claimed priority of language, derived by means of the concept of truth in this sense: “A state of affairs is a real state of affairs if an assertion which represents it is true”.

22In reality, we win the concept of reality independently from that of truth and the final criterion of truth is neither the intersubjective consensus nor an adaequatio rei et intellectus, the agreement of an assertion with reality, but, if you will, an adaequatio rei perceptae et rei intellectae, the agreement of perceived and thought reality, or an adaequatio perceptionis et propositionis, the agreement of an assertion with perception. The specification can be carried even further. The perception that is to be adequate to an assertion is a perception that is merely identified by consistent behavior. Perception as such is always merely subjective. 1 can make known the fact that I distinguish between red and green most effectively by formulating the perception in language, but this seems to fall into the Erlangen Circle. I can, however, make known intersubjectively the fact that I distinguished between red and green in still another way — which is more reliable — by reacting differently to red and green in a text or at a street crossing. And it would not do to object that such reactions are ambiguous. Every verbal utterance is just as indeterminate. It also would not do to object that the reaction is in turn only subjectively perceived and attains an intersubjective existence only via verbal formulation. That two persons understand the same sentence is decided finally in terms of common usage in the same perceptual situation.

23The production of criteria for the reliability of verbal utterances is a central interest of the Erlangen School. Here it must be said that in experimental test situations as well as in everyday life, the observation of the behavior of others counts as being more reliable than the other’s statements. When in doubt one does well to rely on the behavior (the observation) and not on language (the other’s assertions). The reliability problem must be posed prior to the linguistic sphere, in perception, for example when the perceptions of one and the same object via various senses do not coincide. By and large tactile perception counts as more reliable than visual — as in the case of the stick in the water that looks like it is broken. What is the criterion of reliability here? Certainly not “reality in itself”. A system of experience that is as simple and consistent as possible is decisive. An experienced object is held to be “real” in the sense of “being-in-itself” if its modes of givenness consistently coincide. That which not only I, but everyone, everywhere and always, can come back to and which shows itself to be identically the same when it is returned to, counts as being real (cf. Holenstein 1972, 68ff.).

24The transcendental aesthetic, the clarification of the conditions of the possibility of preverbal experience, remains an essential task of tran|scendental philosophy: that is the conclusion of my argument up to this point. Sensuous experience not only precedes language, it founds language and is, al least in elementary forms, codeterminative of its structure. The perception of language sounds is an especially revealing field, first because of its markedly discrete structure, second, on account of its many different modes of givenness (neurological, articulatory, physical-acoustic, labio-lexical, auditory, synaesthetic) and transformation possibilities (writing, spectrography), and third, because of its functional integration in language, whose significance in the form of a “pure grammar” for that part of transcendental philosophy that is traditionally known as “transden|dental logic” can no longer be overlooked.

The underpinnings of predication

25The second, more specific thesis of the Unhintergehbarkeit der Sprache concerns predication. The assertion that predication is one or even the fundamental verbal and cognitive structure, which no other structure precedes, either genetically or systematically, is characteristic for almost all theorists who search for an understanding of language not starting with the structure of experience, that is, from below, but rather from above, from the logic of thought. This is a logicism — comparable to that intellectualism in the theory of meaning that identifies the meaning of a predicate with an object, with a concrete object in the case of a verb (“he drinks” — “he is a drinker”), with an abstract object in the case of an adjective (“the sky is blue” — “the sky has blueness” or “blueness is in the sky”). In both cases a cognitively and linguistically secondary form is used to explicate a primary, founding form.

26This logicistic overestimation of predication can be found from the Port-Royal Grammar up to transformational grammar and analytical philosophy. Among philosophers, the later Husserl (1939, 124ff., 242ff.) is an original and solitary exception. In the apprehension of an object there is an unfolding of this object into individual determinations, which Husserl calls explication and which is known as modification in linguistics. The object appears here as substrate of determinations in a “prepredicative synthesis”. This explication of modes of givenness in which an object appears finds its direct linguistic expression in a head-modifier construc|tion: “red castle”. This determination, in which the object has displayed itself and which continues in “passive coincidence” with the object, is actively apprehended in a second step, ascribed to the object as a predicate and affirmed. The object no longer appears as “substrate of determina|tions”, but as “subject of predicates”. In “predicative synthesis” we are directed to the subject of the proposition, which is apprehended as an object. Only in a third step is either the statement as a whole nominalized to a state of affairs (“that the castle is red”) or the predicate alone to an abstract object (“redness”), thus itself becoming the subject of possible predicates. Among linguists, Kurylowicz (1936), Trubetzkoy (1939), Jakobson (1939; 1980) and Halliday (1977) arc advocates of the secon|dary character of predication. Jakobson (1980) and Halliday (1977) base their claim on the analysis of language acquisition in children.

27The positive thesis of the Hintergehbarkeit of predication has two aspects:

28(1) the priority of nonconstative verbal structures such as calls (“Paul!”) and orders (come!”) to constative verbal structures (“Paul is coming”) and (2) the priority of the adjectival modification of a noun (“red blood”) to adjectival predication (“blood is red”). The first aspect is important for the interpretation of “one-word sentences” in early childhood. Logicians are inclined to interpret holophrastic utterances such as “mama” or “bowwow” as elliptical predications or as predicators that can be asserted or denied of objects, thus as “this is mama” or “you are mama” and “there is a dog”. But the situation and intonation suggest a nonconstative interpretation, in which speech acts such as greetings have the sense “hello, mama!”, wish utterances the sense “I would like to have the (play) dog”, or imperative demands the sense “come, dog!”. Verbs are generally to be interpreted as imperatives, nouns as vocatives or imperatives, and the circumstantial words that play such a large role in the young child’s utterances (“more”, “gone”) also as exclamations or imperatives. There is a series of powerful arguments against the logicistic reinterpretation of vocatives and impera|tives such as “Paul, come!” into constative sentences of the kind “You are Paul. You ought to come!” (cf. Chellas 1969) or “I command you to come!” (cf. Lewis 1970, 54ff.) or even “Peter to Paul: Order. Paul comes.” (cf. Lorenzen 1974, 68f.), and against their derivation as elliptical surface structures from a deep structure with an explicit constative-predicative form.

- Children master vocatives and imperatives long before they are able to use indicators such as “I” and “you”, performative verbs such as “com|mand”, or nominalizations of actions such as “an order”. The assumption of this kind of predicative and nominal deep structure makes the very implausible presupposition that the child who is learning to speak initiates his first speech acts with complicated transformations that, in addition, remain purely unconscious, and comes to be able to do without these transformations only at a later stage of language acquisition. The child masters shifters such as “I” or “you” and uses them as subjects of sentences only after the acquisition of predicative utterances. By the same token, in the earliest explicit predications with a noun as subject the predicate is not another noun, but a verb. This order is characteristic for languages with the three word categories noun, adjective, and verb (Jacobson 1980, 181ff.), thus first “Fido barks”, then “Fido is small”, and last “Fido is a dog”.

- The reinterpretation of vocatives and imperatives into constative sentences explains the structural richness of language in much too simple a manner. According to this account, there is a universal basic form of verbal utterances, that of the constative sentence. All deviations are nothing other than elliptical and merely surface actualizations of this basic form. But this is not so much to explain the functional multiplicity as to explain it away. It is a peculiarity of human language that it allows various intentional modes (speech acts) to be differentiated from one another structurally. Most animal sounds do not allow the possibility of distinguishing modalities. We just do not know whether the whistle of an ibex is to be interpreted indicatively (“Danger approaches”), as an imperative (“beat it!”), or as a hortative that includes the speaker (“let’s beat it!”) or perhaps merely as the expression of a frightening perception (“oh!”). The hypothesis of a constative sentence form behind vocatives and imperatives is compa|rable to the hypothesis of physical waves behind the perception of colors. A (possible) correlation of two specifically different phenomena (the perception of primary and secondary sense qualities in the first case, intentional modi in the other) is misused in the reduction of the one to the other.

- It might be tempting to interpret the child’s “one-word sentences” as functionally not yet differentiated, plurifunctional utterances, compa|rable to an adult sentence such as “it is warm”, which in some circumstances is not only and perhaps not even primarily intended as an indicative constation but as an imperative appeal to open the window. The fact that the child’s forms of speech, as far as we can tell, remain conspicuously monofunctional long after the holophrastic stage speaks against any such interpretation. The child remains unable to attach two different functions to the same form for a long time. A French child first uses the article les exclusively to signal a plurality. To signal a totality, for which purpose an adult too uses les, he always brings in an additional word: toutes les voitures. At times the child takes refuge in ungrammatical forms in order to keep two functions separate, such as nonspecific reference and numerical indication, both of which can be expressed by the indefinite article. Thus, he might say une de vache to indicate that he is talking about a single cow (Karmiloff-Smith 1981; cf. Halliday 1977, 42, 71).

- It might be argued that the correct use of an imperative like

“come!” presupposes knowledge about oneself as subject of the

utterance and about another as addressee of the utterance and as

agent of the action that is to be performed. Thus the derivation of

“come!” from “you ought to come!”. But we must distinguish between

an implicit “knowing how”, which is constitutive for actions and

which comes to direct expression in its performance, and an explicit

“knowing that”, which is based on a reflection on the logical

implications of an action and which is expressed by a constative

sentence. The connection of an action with its constation is an

achievement that is possible only on the basis of the predicative

structure of language.

The apprehension of a complex whole does not presuppose the explicit apprehension of those constitutive components into which a logical analysis might dissect it. The perception of an ink does not come about via a judgmental synopsis of the smallest perceivable discrete color points into a continuous whole. And the grasp of a volume does not require explicit knowledge of the three dimensions of length, width, and depth that are constitutive for the volume and in terms of which it can be defined. An explicit apprehension of the three dimensions and their interdependence in determining size is first necessary with respect to the conservation of the volume. Volume is only preserved when a change in one dimension is accompanied by a change in one of the other dimensions. Apprehension of the conservation of volume comes long after the first grasp of voluminous objects as such. And first there is an explicit knowledge of the components that are constitutive for volume and their demonstrated interdependence.

A similar case is the personal components of a speech act, which arc represented by the pronouns “I” and “you” in a more advanced stage of the acquisition of language. The explicit grasp of their meaning (“I” signifies the sender of the message in which “I” functions as subject, “you” the addressee of the message), including the reversibility of the relation signified by them, is demonstrably not present from the very beginning and is first documented by means of an explicit and correct use in a dialogue. The performance of an imperative speech act does not imply the capacity to simultaneously assert this act of its subject or even objectively nominalize it as a “command”. We are capable of doing many things that we cannot verbalize predicatively. The hypothesis of a constative deep-structure is built on the assumption of an inner representation of the presupposition of a linguistic utterance that is not genuinely verbal (concrete) but rather mental (abstract).

- The real function of a predicative sentence consists in the affirmation (or negation) of an explication (determination, modification, quali|fication, characterization) of an object. There is indirect evidence that the earliest “one-word sentences” are not to be understood as predications in this sense. They are not predications that happen to have a subject that is not verbally expressed but is rather given immediately through the concrete situation. In the early states of language acquisition the child can only answer “yes” or “no” to questions whose answer requires speech acts that have already been mastered, e.g., speech acts with an emotive or conative function such as expressions of feeling or demands, but not information-questions that refer to a state of affairs in a purely cognitive manner. Prior to the appearance of explicit predications, “yes” and “no” appear as ellipses for emotive and conative but not for constative speech acts (“do you want bread? — “yes” ( =“please!”); “should I come?” — “yes” (=“come!”); cf. Halliday 1977, 48ff., 70).

- The interpretation of “one-word sentences” as predications also ignores the second specific achievement of predication, to render possible displaced speech, i.e., information that is not tied to the situation of the speech event. One who has mastered predicative structures can make utterances concerning absent, past, and future, as well as unreal, phantastic states of affairs. As soon as a child is capable of making explicit predicative utterances (noun-verb combinations), it is inclined to make use of the possibility of speaking about the unreal and play with “untrue” assertions (“dog miaow”) (Jakobson 1980, 177f.). If the first holophrastic utterances of the small child were to be interpreted as predications, one would expect to find utterances that do not refer to the situation in which the child happens to be at the moment. The empirical material (the direction of the regard and accompanying motor actions that serve to determine the reference) do not suggest any such interpretation.

29After the acquisition of the constative sentence structure with nominal verb and verbal predicate has freed language from being bound to the given situation in which the speech act takes place, something else is required to express that narrated event that takes place in the situation of the speech event (the identity of time, space, and perhaps also the person of the speech act and the narrated event). This is the task of the so-called shifters. But the shifters do not simply restore the coincidence of the speech event and the narrated event in the same place and the same time, which can be abandoned with the use of an explicit subject-predicate structure. They do this by severing two additional constraints of the earliest verbal expressions. First, they free language from the inherency of the reference-determining properties, from the determination of objects and events, by means of modes of givenness that are inherent to them as qualities. Shifters indicate by means of relational determinations. In the case of reversible relations, they also free the young speaker from his egocentricity. Thus a predicative utterance’s relatedness to a situation by means of shifters, as far as it is freely chosen and made explicit, must be distinguished from a pre-predicative utterance’s dependence on its situation, which is the inevitable result of the inexplicitness and meagre structure of these utterances. Until the reversibility of shifters (I–you, here–there, right–left) is expressed in their correct usage in a dialogue, we do not have a reliable criterion for their being used to designate relational as opposed to qualitative determinations. The shifters are comparable to relational nouns such as “brother” or “neighbor”, since it can be shown that they are not used in a relational manner in the early stages of language acquisition and most certainly not in a reversible sense, but rather in a qualifying sense. In this case, “brother” means something like “little boy” (cf. Elkind 1962). Thus, a qualitative determination that is accidentally coextensional with a relational determination is misunderstood as the meaning of a verbal expression.

30The correct use of the pronoun “I” documents not so much the breakthrough to self-consciousness, as idealistic philosophy has assumed, as the discovery of the intersubjectivity of the experience of the world and verbal activity (cf. Jakobson 1980, 185ff.). The child is first capable of a genuine dialogue when he has grasped the reversibility of shifters, since a dialogue presupposes an exchange of social roles that is specifically linguistic. The proper reaction to an exclamation or a request is not a verbal answer, but rather motor interaction with the greeted object or the active fulfillment of the request. In a genuine dialogue the partners no longer merely interact; they are no longer merely sender and receiver of pragmatic speech acts, but rather the completely specific bearers of information and affirmations. According to Halliday’s observations, which we have already referred to many times (1977, 48ff., 70), the informatory and dialogical use of language go hand in hand. Halliday’s children arc incapable of opening a dialogue or of answering a purely informational question with “yes” or “no” prior to the predicative use of language.

31In languages in which the epithetic and the predicative use of adjectives are morphologically distinguished, the epithetically used adjectives often have a morphologically more complex form. Thus, German signals number and genus only in the epithetic, not in the predicative use of the adjectives. The epithetic application is (with regard to number and genus) marked, the predicative is unmarked. One says: Ein guter Wein or eine gute Milch or ein gutes Bier wird ausgeschenkt, but Wein or Milch or Bier ist gut. The distinction between marked and unmarked is one of the most reliable criteria for deciding questions of genetic and structural priority (cf. Holenstein 1976b, 67ff.). Thus, in the genetically prior and structurally more simple singular of the articles and adjectives, as well as in the third person singular of the personal pronouns, gender is distinguished (der, die, das; guter, gute, gutes; er, sie, es), but not in the corresponding plural (die; gute; sie).

32The epithetic determination of a noun is a form of description that is prior to the predicative description. The epithetic description can exercise two different functions. It can qualify the object being talked about. But it can also determine the reference of the utterance. The child determines the referent with qualifying expressions (“hot milk”) just as early as with deictic means (“this milk”) (Karmiloff-Smith 1981). In predicative description the reference-determining function is abandoned in favor of the possibility of a communication that is situation-independent. The affirmation of a property is an additional function of predicative description. The first perceptual, and then verbal, discrimination of the property “hot” from the substratum “milk” contains no trace of an act of affirmation. The predication qua attribution and affirmation presupposes the discrimination of a particular property of a perceptual object. The immediate verbal expression for a perception that is qualified in a specific manner is not a predication, but a modification. One who unexpectedly sees a white horse does not formulate his perception predicatively: “here is a horse; the horse is white”, but with a modification of the appropriate noun: “A white horse!”.

33The interpretation of two-word phrases (in children) as nonpredicative modifications seems counterintuitive and is a problem even for experi|enced linguists and psycholinguists. But being misled by one’s own intuitions is a familiar phenomenon in cases where the communication partners have a differently developed code. It is not merely that a receiver with an underdeveloped code only takes up a message to the extent that he can grasp it with the rules of his code, that he reduces it to the level of his code. There is also the reverse tendency for a receiver with a more highly developed code to transform a message that presents a state of affairs on a very low level into the highest form of presentation of which he is capable. Examples for this spontaneous “improvement” are to be found at all levels of language, from the phonological through the grammatical to the semantic levels (cf. Holenstein 1976b, 192ff.), but also in extralinguistic contexts, wherever solutions to problems are needed (cf. Rest et al. 1969). A mother tends to raise a child’s two-word utterance such as “banana — good” to the level of adult language in two respects.

34First, she “improves” the modification into a predication, and in addition she “improves” the situational definiteness of reference into a verbal: “Yes, the banana is good”. The effort that is required in order to take up a lower-level communication in terms of a higher level results from the fact that the higher-developed level does not differ from the lower merely in terms of the addition of more elements, but consists in a restructuring of the preceding levels. The differences in the structure of the reception of a state of affairs and the solution of a problem resist a smooth adaptation to the simpler forms of adaptation and problem solution.

35It must be admitted that after a higher stage of cognitive development has been reached a restructuring of all prior achievements can and often does take place. The predicative structure is the fundamental structure not only in the theories of most logicians, but also in the awareness of language of most speakers. A modification such as “white milk” thus seems secondary and derivative compared to “milk is white”, and in certain contexts it even appears to be a deficient, elliptical form of predication and not a structure that is presupposed by predication both genetically and with respect to the truth-theory. It is quite possible that a theory that takes higher levels of cognitive development to be basic will be superior to a theory that does justice to cognitive genesis with respect to the criteria of simplicity and technical applicability. But it is necessary to distinguish between the goals and interests of the sciences, which are oriented toward a maximally economical implementation of technical operations, and the transcendental-philosophical interest in uncovering the conditions of possibility of the basic operations that the sciences take as their point of departure and in the eradication of hysteron proteron fallacies in the foundations of science.

36Since the cognitive hysteron proteron fallacy of a derivation of modi|fication from predication is admittedly something less than obvious for most experts, I would like to demonstrate an analogous cognitive hysteron proteron fallacy by means of another, simpler example, that of the constitution of the series of natural numbers. It is quite possible to think of a system of the series of natural numbers in which rather than the numbers 1 to 9, the numbers 91 to 100 function as basic numbers, and that all other numbers prior to 91 (and after 100) are derived from the numbers 91 to 100. We can use the first ten letters of our alphabet as symbols for these basic numbers: 91 = a, 92 = h, etc. The number our system designates as 1 would be symbolized in this new system by j-i, 2 by j–h, 10, a bit more complicated, by j–a+j–i, etc. This kind of construction of the number system is logically possible (though perhaps improbable, on account of its inelegance, in colloquial as well as scientific usage). But from the cognitive point of view it exhibits a splendid hysteron proteron fallacy. For a finite mind like the human mind, the numbers 91 to 100 are only accessible in terms of the intuitive grasp of the lower numbers 7 to 5 or 6, in the case of a well-trained intuition perhaps up to 10 and 72, and by means of the equally intuitively accessible rules for combining just these numbers. These lower numbers can be logically, but not cognitively, derived from the higher numbers.

The distinction between logical and phenomenological theories of language

37A discussion that takes the results of empirical investigations as its point of departure is certain to be met with the objection that at least in the case of the Erlangen School we are not faced with an empirical-descriptive theory of ontogenetic and phylogenetic language development, but with a normative reconstruction of language-in-use, with the goal of producing a reliable intersubjective system of distinctions that can provide orientation in a world full of conflicts. But this kind of objection assumes, as is unfortunately rather normal in philosophical circles that want to legi|timate the notion of a philosophy of language that is independent of linguistics, that linguistics is concerned with a mere description of individual verbal phenomena, not with the justification of such pheno|mena, and most certainly not in terms of principles that might have an a priori status and thus hold for language as such. The only reply to such an objection is that it is based on ignorance of the real scientific enterprise. In his earliest works, Chomsky explicitly thematized the scientific goal of the explanation and evaluation of competing explanations in the area of the sciences of language. But even prior to Chomsky the concern, and most certainly in the context of linguistic development, was with the discovery of laws that determine the structure of a language (possible universals) and that are thus, in an appropriate direction of interest, normative for this language (cf. Holenstein 1975, 113ff.).

38To be sure, the normative point of view is secondary for pheno|menology and structural linguistics. Universally valid norms for correct thinking and speaking are the result of conditions that hold a priori for thought and speech. These are primarily reflected in purely theoretical propositions, which then provide the basis for the corresponding normative turns. The purely theoretical proposition “A implies B” is the basis for the normative sentence “Whoever says (asserts) A, ought to say BY. It is of course debatable whether normative laws play the same role in a region of phenomena such as language, whose realization is always goal-oriented, as they do in spheres of objects that, according to the classical view, are constituted without reference to practical goals. A speaker always pursues one or more goals, among which that of intersubjective communication is generally dominant. Anyone who wishes to achieve his goal must orient his action in terms of laws that are normative with respect to that goal. But that which is quoad nos primary need not be quoad se primary. And anyone who speaks correctly and understandably obeys laws that are based on the structure of the acoustic material, on the one hand, and on the structure of a pure “theory of meaning” (of the laws concerning the combination and modification of meanings), on the other hand, and that hold independently of their goal-oriented application.

39Philosophers like to criticize scientific attempts to produce a genetic explanation of human knowledge by claiming that such attempts use basic concepts and propositions that are justified merely in terms of their contribution to the construction of theories that are as general, simple, and free of contradiction as possible. The philosopher, on the other hand, is concerned with the conditions of possibility of the cognitive constitution of concepts and propositions that can be used as basic terms and axioms of a theory. The philosopher cannot be satisfied with the (constructivist) statement that verbal actions such as predication and dialogue must be used by any such enterprise, if it is to be able to make a claim to objectivity (which means primarily intersubjective validity). Predication and dialogue cannot be intersubjectively thematized without circularity, without being simultaneously practiced. The deficiencies of traditional transcendental philosophy are brought to light in this insight, which points in the direction of a completion via language analysis, i.e., a transcendental linguistics. True enough, objective justification is only pos|sible in a predicative dialogue. What a trivial discovery! But transcendental philosophy is not merely concerned with the constructive justification of predicates and dialogue in the form of an intersubjective discourse, which is in the last resort oriented toward formal tu quoque or self-contradiction arguments. It is rather concerned with the reconstruction of cognitive achievements that are presupposed by such high-level phenomena as predication, dialogue, and linguistic competence in general. A verbal event has been transcendentally justified when it has been shown to be founded in more elementary cognitive achievements that necessarily precede it, and finally in cognitive phenomena in terms of whose structure it is intuitively transparent that they do not in turn refer to a foundation in preceding phenomena.

40There is more than one reason why this kind of reconstruction of the logical, a priori, or essential structure of language and thought must stick to the factual genesis of language and thought.

- Human phantasy is limited when it comes to discovering all possible linguistic and cognitive phenomena. Even Husserl knew that quite well (a point of which few of his opponents, and, indeed, few of his followers, have taken note): “The facts guide all eidetics. That which I cannot distinguish in examples cannot be won in eidetic distinctions and formation of essences. This is itself an eidetic insight”, as a Husserl manuscript from 1921 puts it (sec Holenstein 1972, 24).

- The preliminary genetic stages of language and thought as they are practiced on the dizzying heights of philosophy and the theory of science are present forms of consciousness that a transcendental philosophy that aims at being a theory of consciousness in general, and does not restrict its efforts of the theory of scientific consciousness, must do justice to.

- Finally, the factual genesis of language and thought is a “genesis according to laws of essence”. There are a priori laws that determine the process of factual genesis, that restrict the number of possible types of process from the very beginning.

41Development in recent transcendental philosophy as opposed to classical, Kantian transcendental philosophy does not consist merely in the linguistic turn, in the linguistic conception of apparently purely logical categories (or some of them), but also in a genetic turn, in the demonstration that not all categories of consciousness are equally basic, that not all have the same genetic status. And this distinguishes the progressive convergence of Husserl’s “genetic phenomenology”, Piaget’s “genetic epistemology”, and Prague structuralism, with its bridge of Saussure’s dichotomy between synchrony and diachrony, from older revisions of Kantian philosophy. These three movements have a genetic and antirelativistic attitude in common, seeing genesis as being grounded by general structural laws.

42There are forms of consciousness that are conceivable and, indeed, in children and sick persons, actually discoverable, in which not all categories that are constitutive for a “scientific consciousness” appear. And here not every arbitrary selection of such categories is possible. Rather, there is a hierarchical order that must be followed. If category A appears, then category B must also be present, but not necessarily vice versa. Thus, we can conceive of a form of consciousness, one that is realized at a certain stage of the development of intelligence, that exhibits the categories of unity and multiplicity from Kant’s table of categories, but does not exhibit the category of totality (which is fundamental for the constitution of scientific statements). A consciousness, however, that exhibits the categories of unity and totality but not the category of multiplicity is impossible. The concept of totality presupposes those of unity and multiplicity, and in point of fact they precede it in the actual development of intelligence and in the corresponding expressions in the development of language (cf. Karmiloff-Smith 1981).

43If predication is claimed to be “nichthintergehbar” (Mittelstrass 1974, 74ff.) because there is no theory and no a priori ground for a theory that would ground it without making use of it, then the same must be asserted mutatis mutandis of the category of totality. There is no such thing as a theoretical proposition or an a priori grounding of a theory in which it is not implied. But hardly anyone would be prepared to assert that a linguistic system that does not have this category cannot be understood. However, the same must be said of a language system or a cognitive system that does not yet exhibit predication. A child on the level of “one-word sentences” and modifications knows by-and-large what he says. Tran|scendental philosophy has the job of showing which selection of categories out of the arsenal of categories of consciousness of an adult person is necessary for the understanding of such child languages, and the order in which these categories can be acquired or which restrictions hold for the successive establishment of a table of categories.

44The fact that the Erlangen School takes little note of the factual genesis of ordinary language in its effort toward an “orderly constructed language” is obviously to be explained by the belief that colloquial languages are “wildly grown” (wild gewachsen) (Lorenzen 1974; also Apel 1963, 24). Explicitly or implicitly, the old nominalistic creed, that all phenomena are equivalent and equally compatible and can thus be bound together into ever more complex phenomena in arbitrary order, stands behind this assumption. Both experience and a priori insight contradict this creed. The most pressing task of a contemporary philosophy of language does not consist in the construction of “an orderly constructed language as a tool for rationally taking stock of the world” in the face of a “wildly grown” and thus unreliable colloquial language, but rather in discovering the ordered structures of natural languages, to the extent that they are hidden by the highly apparent divergences between various languages. Before we construct a normative ortholanguage, we need to investigate the nomogenesis or orthogenesis of natural languages.

45The assumption that natural languages are “wildly grown” (in the sense of not being subject to laws and norms) is absurd in two respects: ontologically and functionally. Ontologically it implies that the most general ontological laws, according to which entities are either compatible or incompatible with one another on the basis of their properties, and if compatible, then are such that they stand in relations of presupposition, entailment, affinity, preference, etc. to one another, do not hold true for language (or, more generally, for culture). But there is no reason to think that such laws only hold for that which has to do with human nature and not for that which man does with this nature, only for physical and not equally for mental phenomena. The impression of wildness, which natural languages can easily awaken, is no more a reason to assume a total arbitrariness in their structure than is the view of a primeval forest a reason to think that such forests cannot be subsumed under universally valid laws. The scientist’s ambition is precisely that of discovering the point from which a region of phenomena no longer appears as an unordered chaos but rather as an ordered cosmos. The thesis that natural languages are “wildly grown” is also thoroughly implausible from a functional perspective. Language is a means of intersubjective understanding and a tool for mastering complex cognitive phenomena. Inter-subjectivity is only guaranteed if speaker and hearer use the same sign for the same phenomena, i.e., if a minimal uniformity is assured. Complex problems, such as the constitution of the series of natural numbers, can only be cognitively mastered if there is a certain unity and order in their designation (Leibniz 1765, §2.16.5). Before one, especially as a convinced pragmatist, dismisses the ideas of universality and of a hierarchical order as metaphysical dreams, it would be wise to consider their possible functional implications.

46There is good reason to orient oneself in terms of the nomogenesis of ordinary language even if one is of the opinion that a special language constructed according to explicit rules is required for the mastery of philosophical and scientific problems: (1) because one makes use of colloquial expressions in the initial stages of the construction of the ortholanguage, if not because of fundamental difficulties, then at least out of convenience; (2) because a comparison of the laws concerning linguistic structure that the constructivists have suggested with the laws that linguistics and its subdisciplines psycho-, socio-, and ethnolinguistics have discovered shows that the sciences that are oriented to natural languages offer a much richer and more differentiated picture of the categories and laws that successively come into play in the building up of a language; and (3) because the progressive working-out of the Erlangen ortholanguage has exhibited a partial approximation to the genesis of natural languages, especially with regard to its first stages. Whereas the first textbook of constructive logic (Kamlah & Lorenzen 1967) took an explicit predicative sentence “This is a bassoon” as its point of departure, the second textbook (Lorenzen & Schwemmer 1975, 29), not unlike the language of the child, begins with an order to do something: “Throw!”. A systematic orientation in terms of the stages of linguistic development might well accelerate, if not spare, a number of revisions.

47After 50 years of attempts to overcome “systematically misleading expressions” by constructing formalized languages, it is high time that two things be taken seriously: (1) the investigation of the extent to which the bewitchment by such colloquial categories does not rest on a lack of knowledge concerning the goals and ways of functioning of natural languages, especially the function of context-sensitive ambiguities of linguistic categories and the plurifunctionality of language in general; and (2) reflection on the ways in which the study of language can be “systematically misled” by the orientation in terms of poverty-stricken logical calculi. The already-mentioned substitution for the predicative verb of an adjective or even a noun (Aristoteles scribit, — est scribens, — est scriptor) is a confusion deeply rooted in 2000 years of philosophical history. A more recent example is the undifferentiated application of the predicate-argument structure for predicative and determinative structures, i.e., for subject-predicate, predicate-object, and noun epithet relations equally, in which categorially different and, in many languages, also structurally univocally differentiated structures are leveled (see Trubetzkoy 1939).

48In phonology, the construction of too abstract phonematic properties on the basis of a one-sided respect for certain ideals of science has led to a rehabilitation of “natural phonology”, whose primary criterion is the psychological (and neurological) reality of the phonological system. Similarly, we need a “natural grammar” and a “natural semantics”. The main criterion for such a “natural grammar and semantics” is the agreement of their structures with the structure of ontogenetic language acquisition, phylogenetic language development, the actual genetic processes of language production, reception, and memorization, and finally with the structure of pathological language disturbances and everyday mistakes. The thesis that lies behind Freud’s epochal discovery, that even faulty behavior is not arbitrary (accidental) but rather has a lawful structure, is also true for language: deviations from laws occur lawfully in their turn (Fromkin 1971). They can have a regressive character and represent earlier stages of development, or a progressive character and anticipate a change that is on the horizon.

49A (constructivist) logical theory of language orients itself primarily toward the criteria of simplicity and unity of the theory. A (reconstructive) phenomenological theory of language, in contrast, works primarily in terms of the agreement of the metalinguistic principles of explanation of the observable linguistic facts with the psychological and neurological, in short with the (in the widest sense) mental principles of the organization of these facts. A linguistic theory (metalanguage) that is restricted to observable verbal utterances (the messages) is a positivistically emasculated theory. The code (the “rule consciousness”) of the language user is a specific phenomenon to which a theory that concerns the total linguistic reality must do justice (cf. Holenstein 1976a, 59ff.). Linguistic pheno|mena are multidimensional phenomena. The observational adequacy of a theory of language is in any case limited, if the genetic dimensions we have considered (onto-, phylo-, and actual genesis) and their various levels (neurological, physiological, and psychological) arc not taken into account. The method of most language theorists who come to language from formal logic reminds one of the physicist who collects the observable input and output data of a standard computer and tries to use them to discover the internal structure of the computer, but without making use of the possibility of taking the computer apart, or investigating prototypes and older, less perfect models, which might provide revealing data concerning the “inside” of the computer. As we all know, the same output data can be derived from the same input data by a variety of very different mechanisms (alias theories).

50The physicist and the logician are interested in the simplest mecha|nism. It is a legitimate interest. The phenomenologist is interested in the mechanism that is actually at work in the computer (alias man). This is an equally legitimate interest. The human mind is by no means a completely impenetrable black box. This is the reason why a phenomenological language theorist sticks close to the psychological data that can provide clues to the code that is actually used by the speaker and hearer. (In addition, of course, there is the secret bet that this code will also turn out to be the simplest one, once we have laid open the multiplicity and intricacy of the functions of human language.)

51A second characteristic of a phenomenological theory of language is adherence to a structure that is inherent to linguistic phenomena (sounds as well as meanings) and situationally invariant, as opposed to the supposedly pragmatic thesis of a totally context-relative variability of these phenomena. It thus turns against empiricist theories of learning, according to which every pairing of a specific phenomenon with a specific motor or verbal reaction is equally possible and trainable. It defends the thesis that what is learned is dependent on the system of cognitive categories that are available and are acquired in a logical order. To take a simple example, the concept “library” cannot be learned unless the concept “book”, which “library” contains as a meaning component, has been grasped. A some|what more complex example has already been mentioned: The category of totality cannot be mastered by someone who has not already acquired the categories of unity and multiplicity, which are (epistemo-)logically pre|supposed by that of totality.

52The thesis that we can get behind language to a prelinguistic, cognitive system of distinctions allows for a separation of two positions, one pragmatic-empiricist and one structural-aprioristic. According to the first position, every distinction is situation-relative. The same object is, de|pending on the environment against which it stands out, interpreted in various ways. According to the second, certain ways of distinguishing arc privileged for structural reasons. The means for making distinctions constitute a hierarchy, for whose order structural relations of compatibility and affinity between the individual phenomena are decisive.

53The pragmatic, relativistic point of view is expounded in one of the pioneering works of cognitive psychology (Olson 1970, 263ff.). A gold star is placed under a small round white wooden block. An observer of this game of hide-and-seek is requested to tell a newcomer which block the star is hidden under. When in the first case a small round black block lies next to the small round white block, he is told: “it is under the white one”; in the second case, when a small square white block is placed next to the block with the star, “it is under the round one”; in the third case, when three blocks are added to the block with the star, a round black one, a square black one, and a square white one, “it is under the round white one”. The pragmatic conclusion that is made on the basis of such experiments is that the decisive thing is not the object that is to be indicated, and not its invariant inherent structure, but the changing context. It would seem that the phenomenologists favorite thesis, that a perceptual object presents an invariant combination of properties, cannot be maintained. Analogous experiments with words seem to refute the parallel thesis of structural component analysis, according to which a word presents an invariant combination of meaning elements. If a subject is told to remember sentences like “the man lifted the piano” and “the man smashed the piano”, the first sentence is more easily recalled when the utterance “something heavy” is offered as a memory prop than when the utterance “something wooden” is offered, while for the second sentence precisely the reverse is the case. The fact that the meaning component “heavy” is contained in the word “piano” seems to be realized first only by means of its combination with the verb “lift”. Conclusion: the signi|ficational content of a word varies with the verbal context in which it is called forth, just as the material content of a thing varies with the situational context in which it is perceived (cf. Hörmann 1977, 179).

54It is striking in Olson, from whom we have the hide-and-seek game with wooden blocks, as well as in Hörmann (1976, 410ff.; 1977, 178ff.), who reports and comments on Olson’s experiment, that both stick to a constant order when listing the attributes of the blocks. The sequence, in English and in German, is “small round white”, “small round black”, “small square white”, and, only in Olson, “small wooden”. The sequence is not, for example, “wooden small”, “round white small”, and “black round small”. Now why just these, and why a unitary order at all? Does this sequence not — in a neutral context in which (as in Olson’s last runthrough) more than one attribute is apparently of equivalent status — indicate that the structure of the properties of an experienced thing as well as the meaning structure of a word might be ruled by constant immanent and not exclusively by changing external factors, although they arc not tyrannized by these factors?

55Accident would have it that a linguist, Seiler (1979), inspired by the Greenberg-Universal 20, but without knowing Olson’s and Hörmann’s psycholinguistic data, investigated the sequence of the same determiners in a neutral context. The Greenberg-Universal 20 (1963, 87) says that when the three determiners, demonstrative, numeral, and adjective, precede the noun in a given language, the sequence is DNAN; if all three come after the noun, the favored sequence is a mirror image: NAND. Seiler found in German (a deep breath presupposed) sequences such as diese meine zehn wundervollen schönen kleinen runden roten hölzernen Kugeln [these my ten wonderful pretty small round red wooden balls], i.e., the sequence of categories: (deictic) localization, (deictic) possession, (formal) number, (subjective) affection, (less subjective) evaluation, (external, easily variable) size, (external, less easily variable) figure, (inherent) color, (immanent) materiality. According to Seiler, the following two rules hold: (1) The domain for the application of determiners of a noun grows with its positional distance to this noun. “Small” is applicable to more categories of objects than “round”, and “round” to more than “white”. Accordingly, their sequential order is, as confirmed by Olson, Hörmann, and their subjects: “small round white”. (2) The more inherent a property is to an object according to a natural (not necessarily scientific) view of things, the closer the corresponding adjective stands to the noun. The less it qualifies the noun and the more exclusively it merely identifies an object (in determining the reference), the further it is from the noun. Thus, deictic determiners stand before formal numerals, the latter before strongly subjective expressions of an affective and less strongly subjective expressions of an evaluative kind, these prior to the adjectives for the external properties of size and figure, and these before the adjectives for inhering properties of color and material. The sequence of determiners mirrors its hierarchy with reference to the noun that is to be determined. In Olson’s experiment, which was undertaken somewhat one-sidedly and interpreted too abstractly, the selection of determiners is pragmatically determined (by the situation and economical considerations — why use two adjectives when one suffices?); in Seiler’s analysis, the sequence of determiners is (in the genuine sense) cognitively determined.

56The development of the sciences of language in the last 50 years is often presented as a (suspiciously accelerated) development from bottom to top, starting from phonology through morphology, which is seldom mentioned, and syntax to semantics. With the contemporary thrust beyond semantics, and thus beyond language in the narrow sense, the road forks. While the one road leads in the direction of a “pragmatic foundation of semantics”, the other leads in the direction of a cognitive foundation of semantics and language in general, which is from a phenomenological standpoint not merely more radical but more correct. While the philo|sophers are still under the spell of their linguistic turn, psychologists have long since made a cognitive turn — a challenge to the philosophers who have reduced consciousness to language, but also to phenomenologists, to renew their philosophy of mind in the light of the new material.